Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Where do you get your ideas?

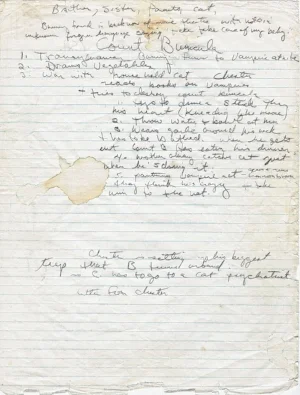

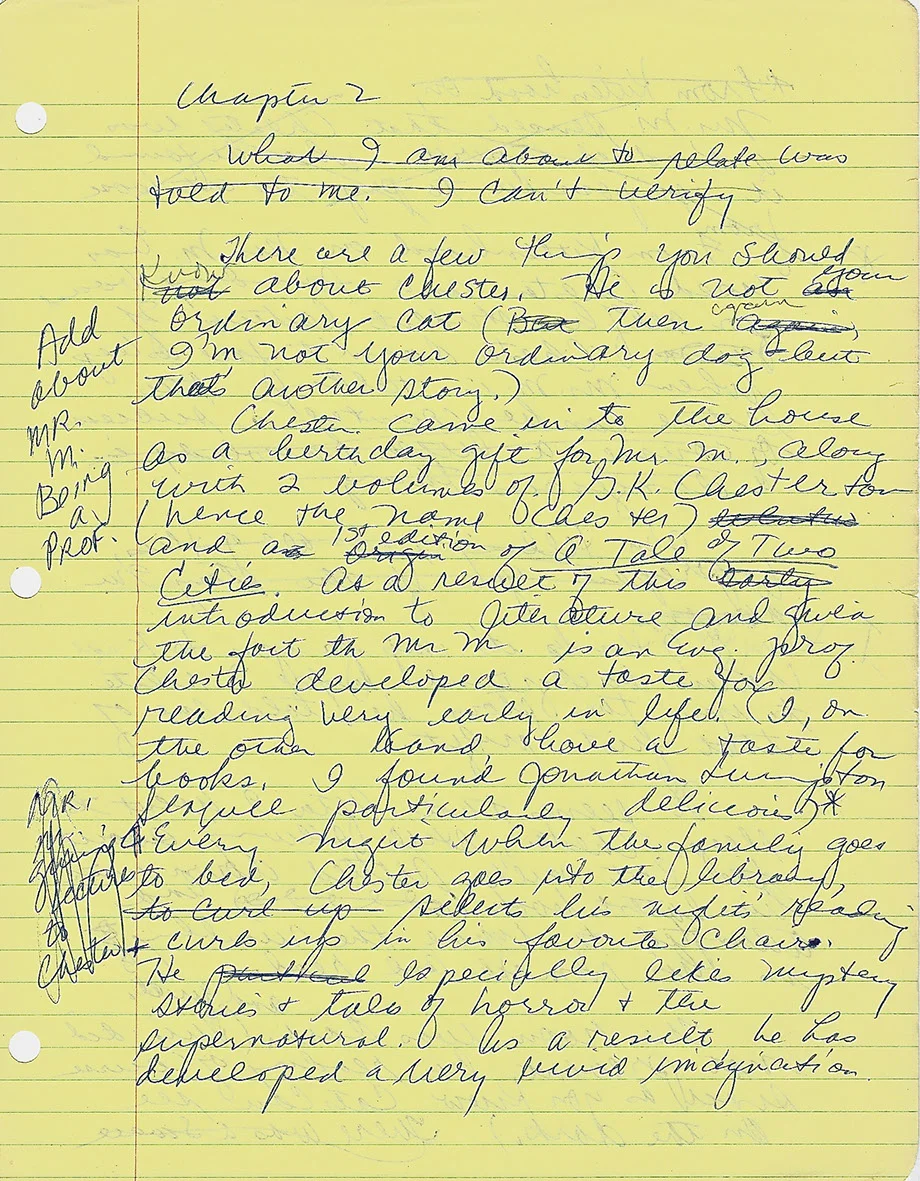

I like to say that I collect ideas, rather than “get” them, because ideas are everywhere. I carry a little notebook and pen in my pocket at all times. That way, wherever I am, if an idea comes to me—from something I’m thinking or something I observe—I can jot it down so I don’t forget it.

How do you think of your characters and their names?

Characters and character names come pretty easily to me. Often, they just appear and I can’t even tell you where they came from. To help myself think of names, I sometimes look through one of several baby name books I keep by my desk.

How do you think of your titles?

Very often (though not always), I have a title in mind before I start writing a book. I’ll have an idea for a book and a title will occur to me. Sometimes the title will change once I’m actually working on the book, and occasionally I have to come up with a title after the book is finished.

I think one of the reasons I’m a writer is that I love playing around with words, so titles and character names are almost like word games to me. My ability to conjure them has as much do with how my brain works as anything else.

Why do you write for children?

I don’t. I write for myself and hope the children who read my books will like what I’ve written.

What is your favorite book you’ve written?

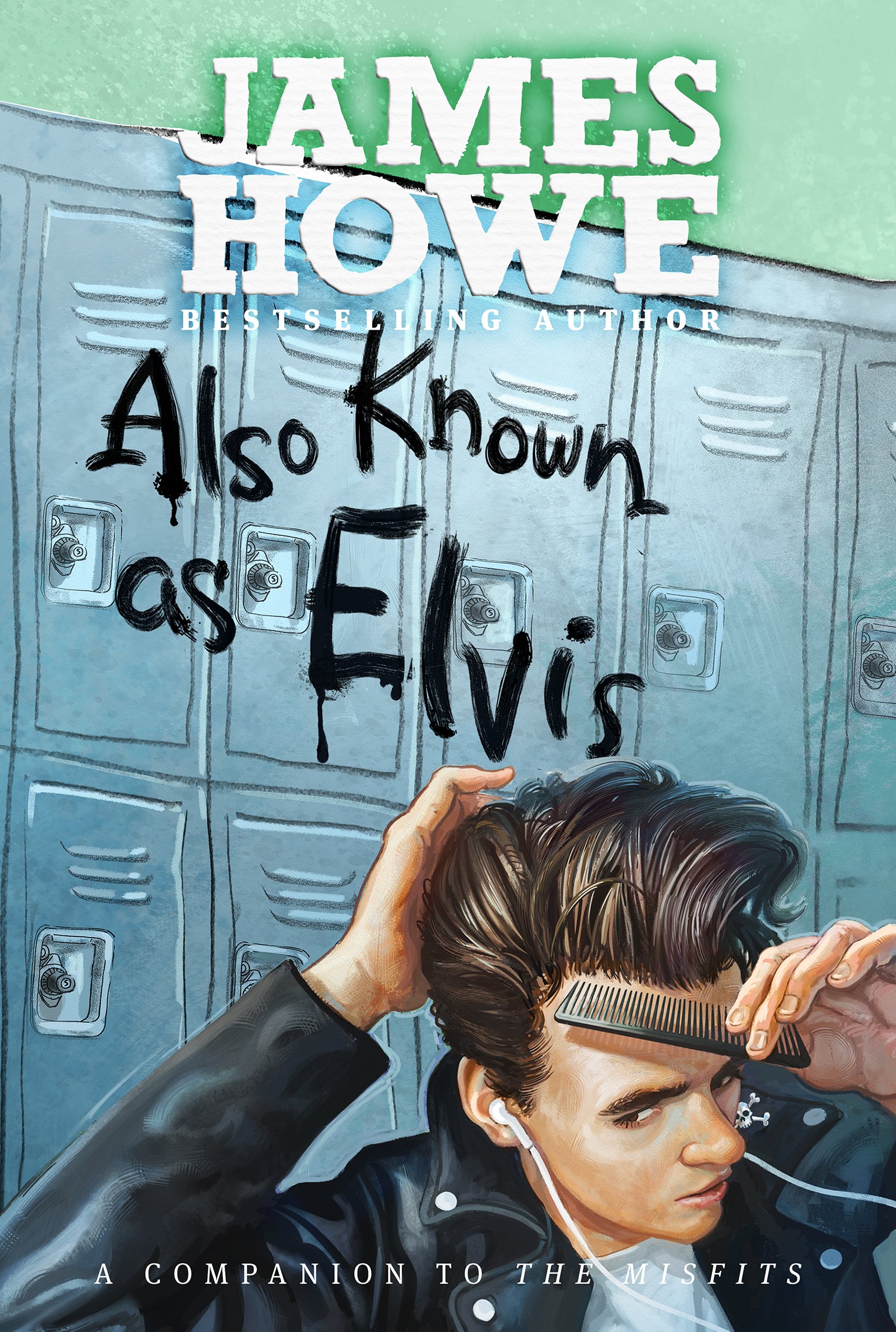

That’s tough. I’ve written over ninety books, from picture books to young adult novels. If I had to choose just one, I’d probably pick The Misfits, not only because I had such a good time writing it and love the characters, but also because The Misfits is read in many schools and is used as a way to talk about name-calling, bullying, and being true to yourself.

I’d have to say Bunnicula is also a favorite, because it’s my most famous and it was also my first. Also, it was in Bunnicula that I first wrote “as” Harold. I’ve written many books in Harold’s voice since then, so he’s really a part of me. And so is Bunnicula. The other book I’d have to say is a favorite is The Watcher, my only book for older teens. I think it’s my best writing.

Oh, and “Jeremy Goldblatt Is So Not Moses” is my favorite story I’ve written. You can find it in Thirteen: 13 stories that capture the agony and ecstasy of being thirteen.

What is your favorite book you didn’t write?

Charlotte’s Web, by E.B. White.

How old are you?

See “What’s your lucky number?” in Infrequently Asked Questions.

What was your first book?

Bunnicula, which was published in 1979.

How many books have you written?

Over ninety. I’ve lost count. (Okay, fine, I just counted. The answer is 94.) (Except, wait, I've written two more books that are being illustrated now, so make that 96.)

How long does it take you to write a book?

It depends on how easy or hard it is to get what I have in my head onto the page. On average, I’d say it takes me close to a year to write a novel, and maybe two to three months to write a picture book or short chapter book. There are wide variations in this. The longest it took me to write a book was four years. That was Addie on the Inside. The shortest time was a picture book I wrote years ago called The Day the Teacher Went Bananas. That one took me half an hour!

How many drafts do you write?

It depends on the book. I do a lot of editing and rewriting as I write, so by the time I have written my first draft I usually have a lot of what I want in place. After that, I may revise two or three times.

Where do you write?

I have an office on the third floor of my house. But I write on a laptop, so I sometimes sit on the couch in the living room. This accomplishes two things:

It gets me out of my office.

It allows me to sit next to my dog.

What is your writing process?

I start with an idea, often a very simple one—a character or a situation. Then I ask questions. Lots and lots of questions. This is how I “grow” an idea into a story. When I feel that I have enough to get myself started, I plunge into the writing. Well, sometimes I wade in. Finding the right tone or voice for the story is often the biggest challenge and it can take time. During this time, I can easily feel:

My idea is garbage.

I’m kidding myself thinking I know how to write.

Maybe I should go to plumbing school or open a restaurant.

When I finally do find what feels like the right way to tell this particular story, I move forward one sentence at a time, one paragraph at a time, one chapter at a time. I go back and forth between writing notes (asking more questions) and writing the story itself. I like to let the story unfold. I don’t outline or plan things out too much, although I usually have an idea of how the story will end. It’s good to have that in my head as I write, because it gives me a destination to reach.

I try not to talk much about a book while I’m working on it, and I don’t show it to anyone until I’ve finished a first draft—unless I’m really stuck, in which case I’ll bring my trusted editor in and ask her to look at what I have so far and offer some guidance on how to proceed.

Does anyone help you write your books?

My editor helps me, but usually only after I’ve written the first draft. I need to keep other voices out of my head when I’m creating the characters and story. I did write my first two books—Bunnicula and Teddy Bear’s Scrapbook—with my late wife, Debbie, but I haven’t collaborated since then.

Are any of the things that happen in your books based on events from your childhood?

For the most part, the things that happen in my books are made up. I’d say my books are based more on the feelings I had as a child than on the events of my childhood. But there are certainly pieces of my life in many of my books. Some of Joe’s stories in Totally Joe are mine from when I was his age and younger. And a number of the Pinky and Rex books are based on my life.

For example, in Pinky and Rex and the School Play, Pinky is forced to wear a leftover cat costume from Halloween as his monkey costume in the play. He feels really bad about this— and about the fact that he’s a lowly, nonspeaking monkey, when he wanted to have the main part. But when the other children in the play forget to stand up at a crucial moment, Pinky hops all over the stage, acting like a monkey, and whispering stand up, stand up, stand up in everyone’s ears. He saves the day! Well, that all happened to me in the fourth grade. Here’s a class picture of me in the fourth grade with one of my favorite teachers, Mrs. Kubrich.