The Misfits Series

PRAISE FOR THE MISFITS

“[A] timely, sensitive, laugh-out-loud must-read for all middle school students and teachers. This book is needed.”

“A fast, funny, tender story that will touch readers.”

“A knockout, one of the best of the year.”

What Readers are Saying

“Thank you for writing The Misfits because it taught me so much about friendship and about being yourself. The book taught me that I didn’t need to be who other kids wanted me to be.”

“Today’s society is all about being ‘normal’ and ‘perfect.’ If you are different you are considered weird, but really you should embrace being different and be you.”

“The Misfits is the best book I’ve read by far.”

“After reading The Misfits, I am starting Totally Joe, and I like it just as much!”

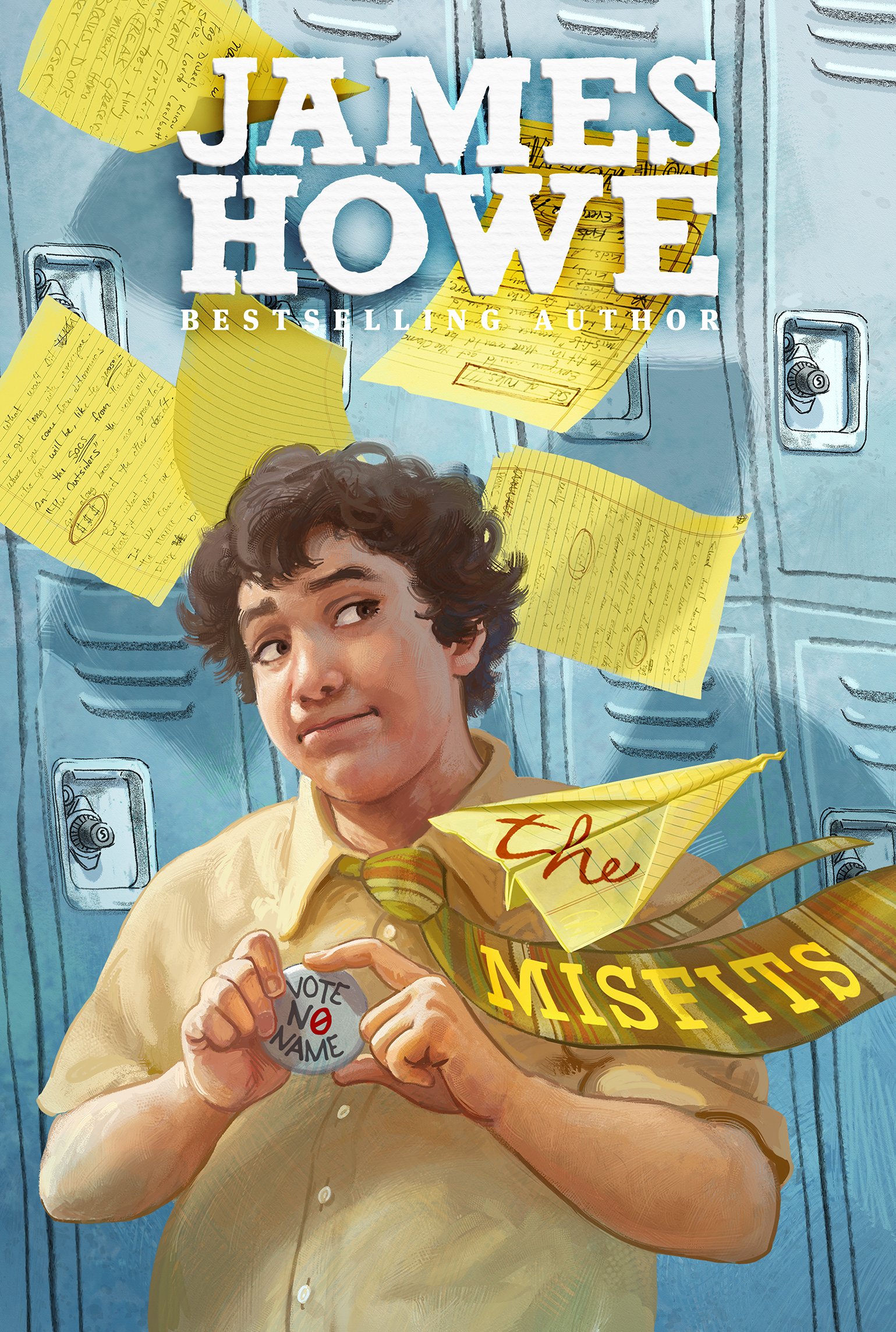

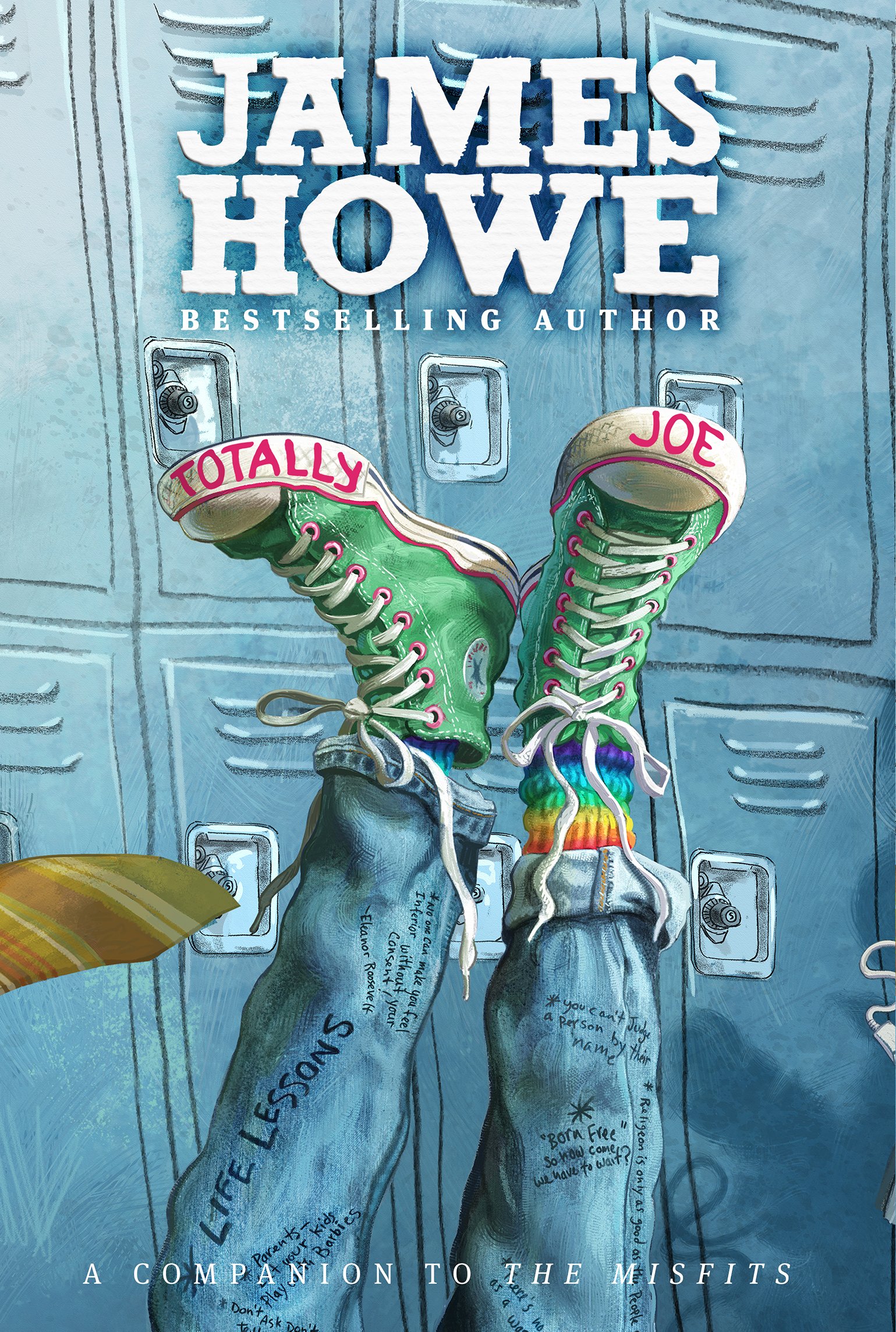

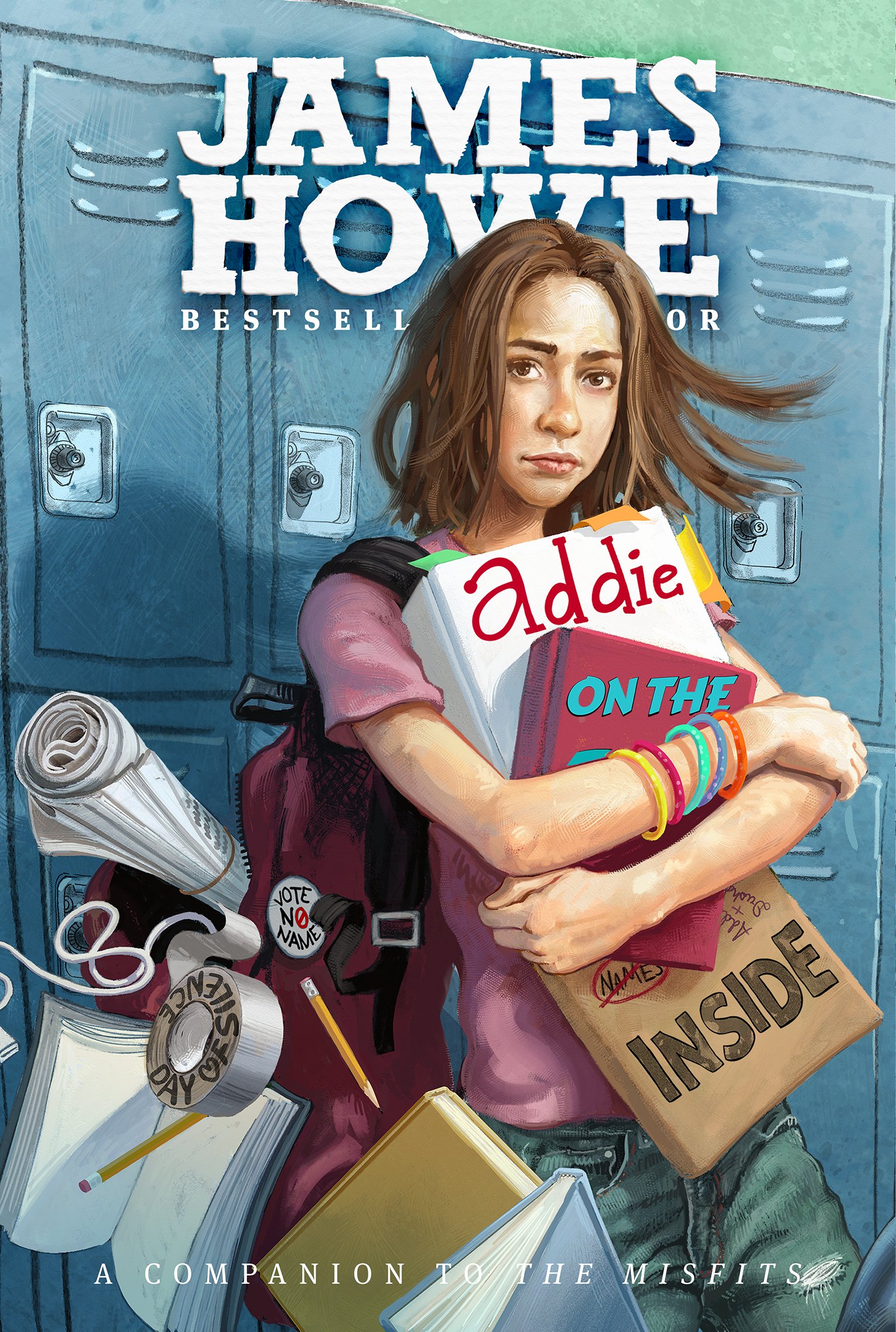

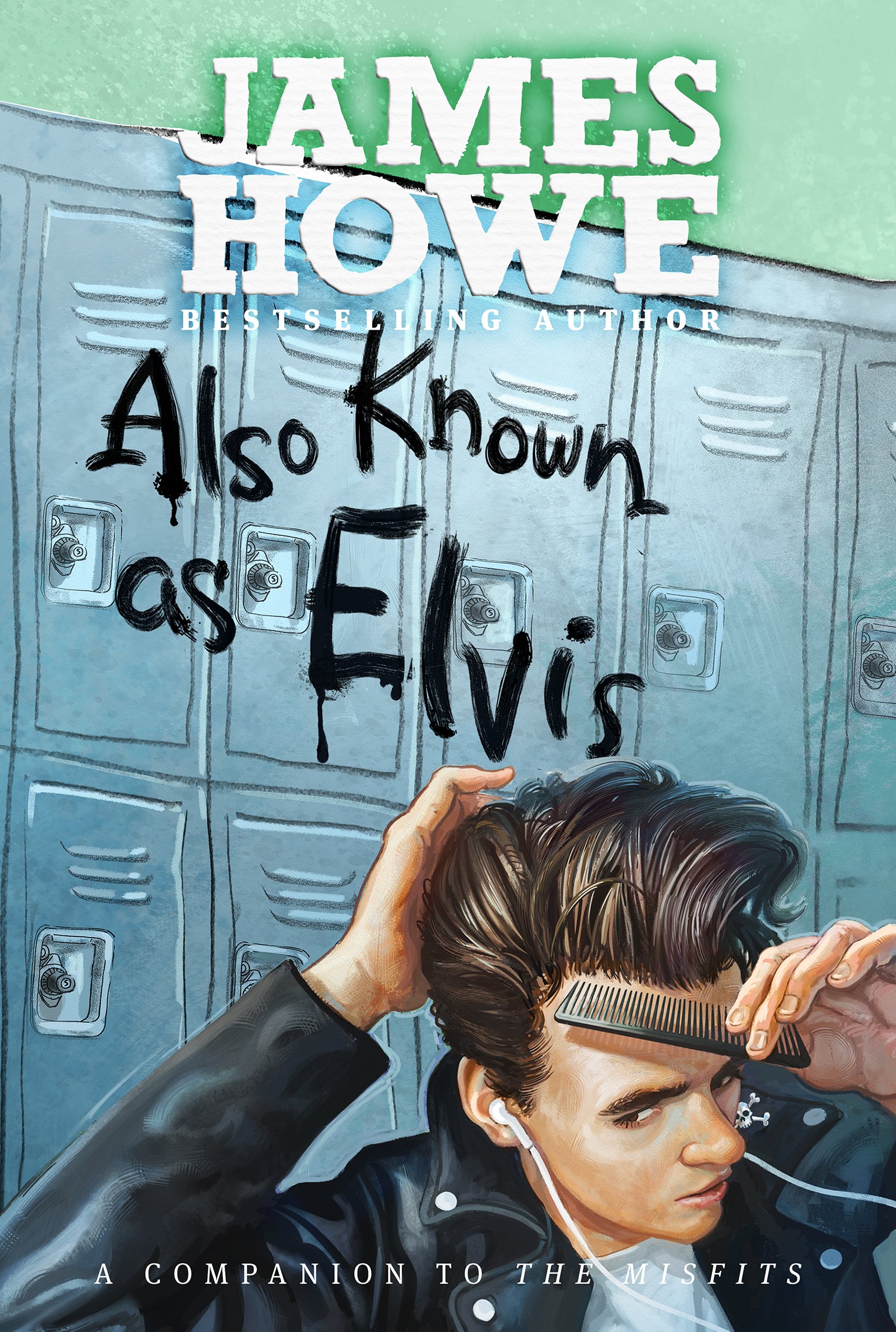

Books in the Series

A FEW WORDS ABOUT THE MISFITS

(Spoiler alert: Plot points are revealed below. Go no further if you haven’t read the book and don’t want to know what happens.)

Adapted from the Author’s Note that first appeared in the 10th Anniversary Edition of The Misfits

The Misfits is dedicated to my daughter, Zoey. It couldn’t have been dedicated to anyone else, since it was Zoey’s experiences in middle school that inspired me to write the book. I’ve shared her story with students in every middle school I have visited since the book was first published in 2001, and with many parents and teachers as well. When I asked Zoey once how she felt about my telling her story to so many strangers, she said, “If hearing about what I went through in middle school helps make things better for even one person, then I feel good about it. I’m proud to have inspired The Misfits.”

I’d like to think that Zoey’s story and The Misfits have made things better for more than one person, but I can speak with certainty only about the one person I know has been changed for the better. That person is me. I don’t think I would ever have called myself “a get-along kind of guy,” as Bobby describes himself before he turns into “somebody who makes a difference,” but I can call myself something I never was before: an activist. Thanks to Zoey – and Bobby and Addie and Skeezie and Joe – I regularly find myself speaking in schools and at conferences to young people, parents, and educators – speaking up for what I believe, speaking out against name-calling, bullying, and homophobia.

When I set out to write the book, I had no idea that this it where it would lead. An unfinished short story I rescued from a drawer gave me the characters of Skeezie and Bobby (who had a different name that I’ve since forgotten); the little town of Paintbrush Falls, New York; Awkworth & Ames Department Store, where a twelve-year-old boy was working, for reasons unknown (even to me), as a tie salesman; and, across the street, the Candy Kitchen and its “back booth with the torn red leatherette upholstery.” There, the “gang” waited. But who the gang was, or what they were waiting for, I didn’t know. I took that unfinished story and let it lead me where it would – to Addie and Joe and the Forum and Kevin Hennessey and Ms. Wyman and Aunt Pam and Addie’s refusal to say the Pledge of Allegiance. I remember writing that scene – when Addie refuses to say the Pledge – as the moment I knew that the novel would go in a political direction, and it would be Addie who would be the driving force.

I’m often asked what elements of the story are real. So:

Paintbrush Falls, New York: not real, but based in part on the town of Webster, New York, where I grew up. Webster is near Rochester, in the western part of the state. For some reason (possibly to do with my moving from Webster in the seventh grade), I mentally picked the town up and relocated it to the northeastern part of the state near Saratoga Springs and Albany.

The Candy Kitchen: real. Not only did the Candy Kitchen in Webster have booths and burgers and ice cream, it sold handmade chocolates (hence its name). As a lover of chocolate, do I have to tell you that the Candy Kitchen was one of my favorite places?

Awkworth & Ames: real, except for the name. There was a little department store across the street from the Candy Kitchen in Webster, but I don’t remember what it was called. “Awkworth & Ames” just came to me as I wrote.

Skeezie Tookis: Skeezie’s name also came as I wrote, as names often do for me. He is not based on anyone real, however. A character who is real is Aunt Pam, who is modeled on my niece Pam.

Joe Bunch: Joe is partially based on someone real. I’ll get to that in a minute.

The Misfits was a surprisingly easy book for me to write. Once I had my four main characters and the basic situation, I just let them go where they wanted to and enjoyed the ride. This isn’t to say that I didn’t think and plan and plot. I did, but with greater ease than I’ve known in writing most of my other books. I loved the characters from the get-go. They quickly came to feel like old friends; it was almost as if I was the fifth member of the Gang of Five. So spending time with friends was one reason the writing went so smoothly. The other was that I cared deeply about the subject matter of the book. And I cared especially about the character of Joe.

When I’m asked which character I am most like, I usually say, because it’s true, that I have a bit of each of them in me. But the greater truth is that I was most like Joe when I was growing up, although I lacked his self-confidence and wasn’t as “out there” as he is. But I acted “more like a girl than a boy much of the time,” as Bobby says of Joe. And like Joe, I am gay. I was gay when I was twelve, too, but I didn’t have the words to understand it or feel good about it back then. The only words I knew were bad ones, bad in the sense of telling me that I was bad. As I have Mr. Kellerman say, “I believed every name I was called in school and took them with me into the rest of my life.” It took many years for me to realize that the names I had been called when I was growing up had everything to do with others and nothing to do with me. When I finally came to feel good about who I am, I was angry that I had wasted so much time believing the lies that others (much like the fictional Kevin Hennessey) had insisted were true. I decided to rewrite my own story, so to speak, by creating a character who is growing up gay and feels good about who he is, who is the person I might have been had I grown up in a different time with different role models. Role models like Joe Bunch.

It wasn’t until I had almost finished writing the book that it occurred to me that schools might take it upon themselves to establish their own No-Name Day, as the characters in The Misfits do. Not only did individual schools in different parts of the country do exactly that within months of the book’s publication, but a national organization working to make schools safe for all students contacted me about creating a national No Name-Calling Week, using The Misfits as its inspiration. When I was asked if I would be a part of this initiative, I jumped at the opportunity. Along with forty other organizations, GLSEN (the Gay, Lesbian and Straight Education Network) has sponsored No Name-Calling Week since March 2004.

The Misfits and No Name-Calling Week have occasionally come under attack for being part of the so-called “gay agenda,” whatever that’s supposed to be. But the number of schools where the book is read as part of the Language Arts curriculum or as an “all-school read” and those participating in NNCW far outnumber the few individuals or communities that find the messages of inclusion and respect somehow threatening.

The real agenda, if there is one, is to make schools a place where everyone can be who he or she is, without having to fear ridicule or attack. The first time I spoke about these issues was at Merrill Middle School in Des Moines, Iowa, during the first No Name-Calling Week in 2004. I spoke across a vast gym floor to 650 sixth, seventh, and eighth graders arrayed in bleachers before me. I’ll be honest: I was terrified. But when I finished speaking, something happened that had never happened to me before. The students gave me a standing ovation. All day long I met with small groups, and later I received letters, and what I heard over and over was this: You told us the truth.

I have always believed in the power of language. Words can hurt. Words can heal. Words can effect change. Words have been what I have worked with for over thirty years now. I’ve written over ninety books and more speeches than I can remember. After The Misfits I wrote Totally Joe, to tell Joe’s story, Addie on the Inside, to tell Addie’s, and Also Known as Elvis, to tell Skeezie’s.

How easy it is to effect change in fiction. One hit of the delete button and a quick rewrite and Presto! the fate of an individual or an entire community can be reversed or set on a whole new course. It is far from that easy in real life. But I hold fast to my belief that each one of us can effect change in whatever ways are open to us. I am lucky to be a writer, to have opportunities to use my words to reach others. The words I used to write The Misfits have changed my life and may have changed others. But if I were not a writer, I hope I would still be aware of how words can make a difference. What I say and how I say it – even one word – can affect how others see themselves and look at the world.

Do books change the world? Maybe. Maybe not.

But one thing is certain: People do.