Writing Bunnicula

I wrote Bunnicula with my late wife Debbie. This is our story and the story of how that book—my first and still my most popular—came to be written.

It was spring, 1977, just after dinner, when we sat down at our kitchen table, the wooden table I had painted a bright tomato red soon after we’d married, and began to write.

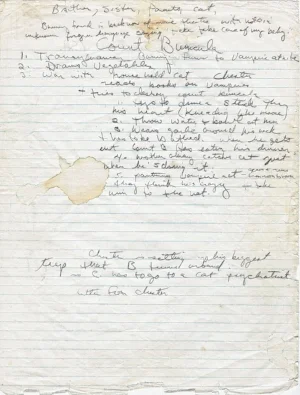

The words "Count Bunicula" in Debbie's handwriting

I still have the scrap of paper from that evening. The misspelling and handwriting are hers: her scrawl, so like tangled hair it was sometimes impossible to decipher. Were we drinking coffee? There’s a stain on the paper that leads me to believe we were. I see—or imagine I see—the look in her eyes that said: Who are we to think we can write a book? Who were we indeed?

Debbie and I were thirty when we began writing Bunnicula. We had met twelve years earlier as freshman theater students at Boston University and had become good friends. Had we met as children we would likely have been friends even then. Born ten days apart in 1946, we grew up in different worlds, but we had a great deal in common.

Debbie and me as children

We both loved words and weren’t shy about using them. But Debbie was—and would always be— far more of a reader than I. From an early age, she read quickly and with understanding. As an adult, it wasn’t uncommon for her to read anywhere from ten to twenty books in a week. When it came to reading, I was the tortoise to her hare. If I managed to read one book in a week it was an accomplishment. Besides, when I was a boy, my favorite reading wasn’t books but comics and Mad magazine.

We were both writers as children. Writing was for me a natural extension of the kind of make-believe play I engaged in with friends or by myself. Debbie, too, liked to act out the movies she’d seen or fantasies conjured from books or real life or thin air. She and her younger brother whiled away many hours spinning stories together in the backyard of the Smith family’s home in Newton, Massachusetts. This would have been around 1954, 1955, when I was living in Webster, New York. At that time, I was in the fourth grade, playing the part of a monkey in a class play about the jungle, head over heels in love with my teacher, Mrs. Kubrich. My weekly allowance of twenty-five cents I spent at Bowman’s Candy Store on one comic book—Archie, usually—and fifteen cents worth of penny candy (strips of candy buttons, wax lips, jawbreakers, tiny tins of fudge eaten with tiny tin spoons). While Debbie was in the Brownies, I was in the Cub Scouts, but only for a year. It felt too much like the army, and besides, I was such a chatterbox I couldn’t stop talking long enough to finish the birdhouse my fellow scouts completed with ease.

It was in the fifth grade, I think, that I was so taken with the idea of vampires that I co-founded—with my best friends Terry and Judy—a club called the Vampire Legion. Membership: 3. I don’t remember much about the Vampire Legion other than meeting one time in somebody’s basement (Judy’s, I think), where we turned off the lights, turned on flashlights, and made weird faces at each other. We also published a newspaper called the Gory Gazette. I was the editor. Circulation: 3.

I don’t know where the fascination with vampires came from, since I don’t recall liking horror movies unless they were played for laughs. Debbie loved scary movies, even as a child, but I preferred movies that were funny—Abbott and Costello; Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis; Francis the Talking Mule. I admit it: I was a major Three Stooges fan. I just liked to laugh. Growing up in a house of jokers, I got to laugh a lot.

My mother loved to laugh, too. I remember her sitting at the kitchen table in Webster, with her husband across from her and three of her four sons—myself and my brothers Dave and Doug—completing the circle. My oldest brother, Lee, had gone off to college when I was four. I hear my father say, “I heard a good one today.” And the joke-telling begins! My brothers pitch in with jokes they’ve heard. They astound me. They all have new jokes to tell. Where do they get them? Why is it that I never have any new jokes? It could be because I couldn’t then—and still can’t—remember jokes to save my life, but it also could be that I just didn’t hear them. How was it that they did? How did they manage to come to dinner every night with new material?

I had to do something about it—and I did. I trooped off to the school library and checked out books of jokes and riddles. And every night at six I arrived at the kitchen table armed and ready. Most of my offerings were interrupted by one of my brothers shouting out the punchline or, worse, greeted with stony-faced silence. They were a punishing audience, putting me through an apprenticeship, forcing me to earn my laughs. But when I did manage to get a good one across—ah, the satisfaction! What I discovered was that I didn’t really need the joke books. I was a fast thinker—I had to be, growing up in that house—and I often managed to come up with something all my own that made everyone laugh.

I was told I had a “way with words,” and my mother always said, “You should be a writer when you grow up.”

But I didn’t want to be a writer, even though I loved to write. From the time I was ten, I wanted to be an actor. I lulled myself to sleep every night plotting out in great detail the movies I would star in, scripting the interviews and acceptance speeches I would give . . . writing, writing, rewriting in my mind. But I didn’t think of it as writing. No, it was all in the service of something greater than words: my own glory!

Christmas, maybe 1955. My mom is at the far left and my dad is sitting in the armchair at the right. My brothers are Doug, next to my mom; Dave, with the hipster mustache; and Lee, leaning forward next to my dad. And yes, that's me, making a face for the camera, with my new Jerry Mahoney dummy. At the time, my dream was to become a ventriloquist.

Had Debbie and I known each other then, she would surely have joined in the fantasy, for I have little doubt that she, too, had dreams of being famous. What was it that was so alluring about the spotlight for both of us? Was it a product of having “famous” fathers? Debbie’s father was a well-known newscaster at WOR Radio from the time the family moved to New York City in 1958, when Debbie was twelve, until he retired years later. My father, while not known to as wide an audience, was an outspoken community leader, first in the Rochester, New York, area and then in Schenectady, New York, where my family moved in 1958. My father was a minister whose activism and liberal views on civil rights, the peace movement, and other social issues of the day made him a highly visible and frequently controversial figure.

Debbie and me with our fathers

If having the particular fathers we did accounted in some part for the attraction to the spotlight we both felt, it also may have accounted for other things we had in common. Our love of words, for instance. Words were an integral part of our fathers’ work. For Debbie’s father, the exact use and meaning of words was crucial; the misuse of one word could distort the truth or slant a news report. For my father, words were the very tools with which he constructed a relationship with his congregants and community. Words were used to heighten consciousness, to inspire, to build the bridge between silent thoughts and meaningful actions. My father had studied preaching in its heyday, and he was masterful at it. I may not remember the contents of his sermons (I was too busy counting the squares in the church ceiling or the ladies’ hats while he spoke), but I must have been listening, because to this day I can feel his style within my own. There are times I’m writing when it is almost as if his hands were guiding mine.

Because of our fathers, Debbie and I both grew up with an awareness of the world’s problems and a sensitivity to its injustices. While religion played a larger part in my life as a child, Debbie’s Jewishness played a part in shaping her sensitivity to the plight of the outsider and to the occurrence of injustice. Always protective of her little brother, she was ever on the alert for a perceived unfairness done to him or anyone else she cared about, and if she did see an injustice being done, her defense of the victim would fly from her—passionate, eloquent, dramatic, and heartfelt.

But her sensitivity to injustice and what it was to be an outsider went deeper and was more personal than mere social awareness. For despite her beauty and her sophistication, Debbie wasn’t comfortable in the world. She saw herself as different, as an outsider trying to find a way in. I, too, was an outsider. My ease with words, especially in making others laugh, and my hunger for the spotlight masked a shy, sensitive, nonathletic boy who was afraid of being seen as different, of being mocked or excluded. Words were my power, as Debbie’s beauty was hers. Words—read, spoken, or written—gave both Debbie and me the tools to try and find our way into a world where we didn’t feel quite at home and the language with which to dream.

Our common dream of becoming actors carried us through high school to the Boston University School of Fine and Applied Arts where, after three years of being friends, we felt our friendship grow into something more. We moved to New York after graduating in 1968 and married in 1969.

Along the way, we acquired two cats. Debbie named hers, a delicate-looking, long-haired gray tabby, Ganymede, from Shakespeare’s play As You Like It, revealing her romantic, theatrical nature. I named mine, a tiny white kitten we thought was a female, Moose, revealing my warped sense of humor. Sadly, Ganymede died from unknown causes only a year after we’d gotten her from the animal shelter. Moose, who lived to be thirteen, revealed his true gender and in a very short time grew from petite to extra-large, fully justifying the name I’d given him.

While living in our first apartment in Brooklyn Heights—just across the Brooklyn Bridge from Manhattan—Debbie and I acquired another cat to replace Ganymede. This one, a pretty but vacuous and tirelessly irritating part-Siamese Debbie named Gudrun (after a character from D.H. Lawrence’s novel Women in Love), rounded out our household for several years. Moose never entirely took to Gudrun. He would terrorize her by stationing himself about six feet away from their food dishes and cackling at her every time she tried to eat. When it was his turn to eat (we assumed Gudrun successfully managed to get nourishment by tiptoeing to the food dishes when Moose was napping in another part of the apartment), Moose would often line up his catnip mice at the side of his dish to keep him company. We never knew if he did this because he was pretending he was throwing a dinner party or because he was imagining the mice were on the menu.

Moose in particular inspired us as we created the character of Chester. While writing the sixth book in the series—Bunnicula Strikes Again!—I found myself recalling, over twenty years later, the time I pulled what I thought was a tiny bit of string out of Moose’s mouth, only to have it uncoil for about ten feet. Harold’s recollection of Chester’s looking like a tape dispenser is a mere transposition of the words I remember thinking about Moose at the time.

But, as Harold would say, I digress.

I was talking about the post-college years in New York, when Debbie and I were in our twenties and trying to figure out what to do with our lives. Having decided I wasn’t a terribly good actor and thinking it might be nice to earn an actual living, I set my sights on getting a graduate degree in psychology and becoming a psychotherapist. I went back to school during the evenings to earn undergraduate credits in psychology, took typing jobs during the day to pay the bills (thank goodness for that touch-typing class in high school), and stayed up late most nights watching old movies on TV with Debbie.

There were no DVD players or VCRs, no cable television, in the early to mid-1970s. But there was The Late Show at 11:30, and The Late Late Show at one in the morning, and The Late Late Late Show after that. These weren’t talk shows; they were movies. Debbie and I stayed up many a night to watch our favorites—The House of Usher and The Pit and the Pendulum, among other adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe stories produced and directed by Roger Corman and frequently starring Vincent Price; and anything, anything at all, produced by the British “house of horror,” Hammer Films. These movies, many of them vampire variations starring Christopher Lee, were scary, funny, and often screamingly bad. We loved them beyond reason. We also loved non-horror movies: Sherlock Holmes mysteries starring Basil Rathbone as the famous sleuth; the Marx Brothers’ comedies; and the song-and-dance extravaganzas of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. But it was the vampire movies of Christopher Lee—Dracula: Prince of Darkness; Scars of Dracula; Dracula Has Risen from the Grave, to name a few—that we were willing to stay up until three in the morning to watch, risking bleary eyes and late arrivals at whatever typing job was currently helping to keep the bill collectors from the door.

Debbie worked at an odd assortment of jobs at this time, most of them related to the fashion industry. Neither of us was excited about the work we did, so when my applications to graduate school in psychology didn’t pan out, we decided to take another stab at making a living in the theater.

Our return to show business took us to an outdoor summer stock theater in Danville, Kentucky, called the Pioneer Playhouse. Only in our mid-twenties, we were cast as the leading man and leading lady of the season and given the opportunity to play everything from young love interests to a middle-aged couple to octogenarians. It was a glorious summer.

Summer 1971, Pioneer Playhouse. Me, as a young suitor in a play by John Boruff called The Loud Red Patrick.

Debbie, wearing the kind of beautiful period costume she loved, in Moliere's classic farce, The Imaginary Invalid.

The two of us, relaxing during a rehearsal break.

Returning home to Brooklyn with new friends and a renewed sense of ourselves as theater people, we threw ourselves into the task of finding work as actors. We had photographs taken. We read the casting papers and showed up for auditions. We both tried getting work as models; ironically, I was the one to succeed. For a year I worked steadily as a model in ads that appeared in magazines all over the country. To my relatives, at least, I was famous!

Our professional acting photos, called "head shots." Debbie took the stage name of "Franklin" in honor of her grandfather Frank. My photo caught the eye of a modeling agency and led to my brief career as a model for national magazine ads.

In some ways, the most important thing that had been restored to us that summer in Kentucky was a sense of play. With our newest best friends, Annie and Lawrence, who also lived in Brooklyn, we passed many an evening entertaining ourselves by improvising silly song parodies, mock epic poems, absurd plays, and spoofs of TV commercials. When we tired of playing, we speculated endlessly on what our lives might yet become; we still felt a long way from being grown-up. We were children at heart, children at play, the four of us.

And Debbie and I, we were children in adult bodies who, in the spirit of play, would one evening a few years later begin to write a book. We were actors, used to transforming ourselves into other characters, practiced at imagining our ways into other lives, other skins. We were readers. We were writers, but not writers who took themselves seriously. We were watchers of countless horror movies and comedies and musicals spun of tinsel and silk. We were cat-lovers and chocolate-lovers and believers in magic.

A belief in magic is required if you want to be an actor, but it doesn’t pay the rent. While I did have my modeling work, the occasional job as a movie extra, and acting stints off-off-Broadway where the salary was subway fare, I still needed those typing jobs to put dinner on the table for Debbie and me, and tuna on the floor for Gudrun and Moose and his lineup of catnip mice.

In 1975 I accepted a job offer from the woman who ran the literary and theatrical agency where I had been working as a temporary typist. At the same time, I wasn’t about to let go of my dreams. I just had to pursue them on evenings and weekends. Having become more interested in directing than acting, I went after every opportunity I could find to direct plays at community theaters, on college campuses, and off-off-Broadway.

Debbie frequently acted in the plays I directed and she tried to find other work as an actress, but her efforts were thwarted by the illnesses that had plagued her from the time she was a very young child. She was frequently sick with one thing or another; even the common cold hit her harder than it did most people.

When she was ill, books were her best companions. I can picture her, stretched out on the sofa in that apartment at the top of the brownstone in Brooklyn Heights where Bunnicula was begun, a box of tissues beside her, Gudrun curled up on her lap, a book open in her hands, and there, always within reach, a stack of books waiting to be read.

Over the next couple of years, I continued working for the literary agency by day, and many of my evenings and weekends were taken up with attending plays and movie screenings that were work-related. Somehow, I found the time to take classes at Hunter College, where I was working toward a master’s degree in theater, and to direct plays, and to act as the artistic director of an off-off-Broadway theater called Theatre-Off-Park. As if this weren’t enough, my courses at Hunter included a playwriting seminar, where I studied writing for the first and only time, and for which I wrote two full-length plays. It was during this period that the inspiration for Bunnicula came to me.

The idea for the character of Bunnicula was mine, but the idea for turning the character into a book was Debbie’s mother’s. I honestly don’t remember where the character came from, but my guess is that my almost instinctive sense of parody was inspired by all those late-night vampire movies—with perhaps a little help from the Marx Brothers and a dash of seasoning from Sherlock Holmes and his colleague, Dr. John Watson, who would ultimately and unconsciously serve as models for the detective team of Chester the cat and Harold the dog.

In the beginning, there was only Bunnicula; and he was nothing more than a free-floating character in my head who, on one occasion, served as material for a homemade birthday card. At some point, Debbie told her mother about him.

My birthday-card drawing of Bunnicula.

“A vampire rabbit,” her mother said. “What a wonderful character for a children’s book. The two of you love to write. Why don’t you try it?”

“Sounds like fun,” was my response when Debbie told me that night of their conversation. And so we cleared the dinner dishes from the tomato-red table in the kitchen, and put words on paper for the first time.

The handwritten words "Transylvanian bunny turns to vampire at nite."

We knew next to nothing about children’s books. What we set out to do was write a story to entertain ourselves, not imitate someone else’s style or figure out what we were supposed to do when writing for children. We gave little thought to being published, none at all to establishing careers as children’s book authors.

That first scrap of paper held all the main ingredients of the book save one. There’s no mention of Harold, only of Bunnicula’s “war with household cat, Chester.” But Chester’s means of foiling Bunnicula—and therefore most of the plot of the book—are listed in neat numerical order and are all based on legendary methods of destroying or defending oneself from vampires: garlic, immersion in water, driving a stake (steak) through the heart.

Whether we discussed Harold or not that night, I don’t recall. All I know is that when I returned from work late the next evening, Debbie had written the beginning of the story—and there on the page was Harold come to life, with his tired old eyes and distinctive voice.

Moose, in the foreground, with Gudrun behind him, in the living room of the garret apartment in Brooklyn Heights where Bunnicula was begun. Much of the first draft was written on the sofa at the right.

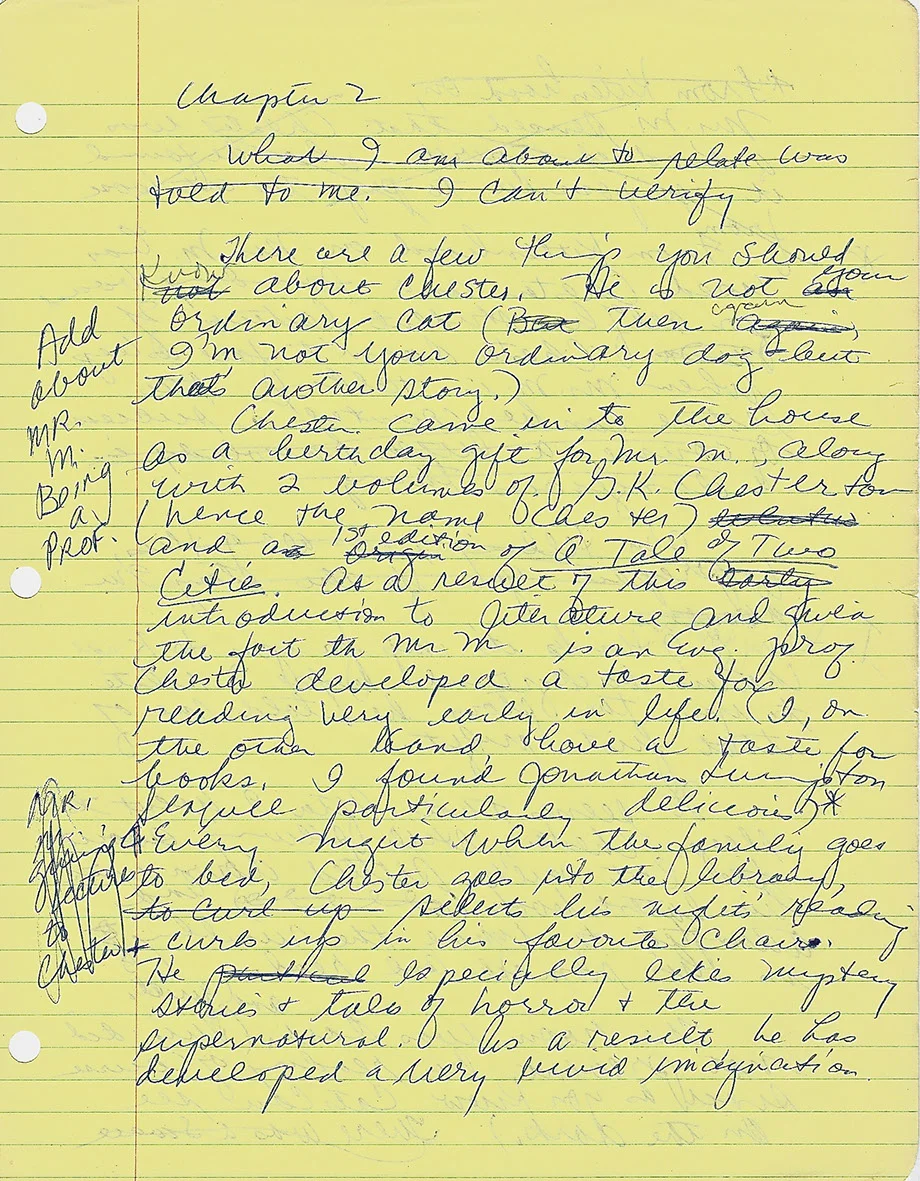

From that evening on, our working method remained much the same. We settled into a comfortable place to work, most often at either end of the living room sofa, and talked the story through. Using a pad of lined white paper, soon to be replaced by a three-hole notebook of yellow lined paper, we took turns recording the words that flew so quickly out of our mouths. It wasn’t easy for whoever was writing to keep up, but how easy I remember it being to spin that story from our imaginations.

We wrote no character histories, did none of the kind of prewriting I so often do now for my novels, just put a few notes down on a single sheet of paper and began to play. Looking at that first handwritten version of Bunnicula, I can spot something I know was Debbie’s (the Romanian sheet music) or mine (Chester’s kitty sweater with the sixteen purple mice), but more often than not, I don’t know who was responsible for what. There were many times that one of us began a sentence and the other finished it.

Most of the first draft of the book reflects the final version. There were very few substantial changes. Toby started out being the older, more obnoxious brother; Pete, the younger, smarter one. By the next draft, they had changed places. And although we never wrote him as such, we at first envisioned Bunnicula to be a different sort of character from the one who evolved—one who spoke, for starters—and one who was much more a traditional vampire, malevolent and bloodthirsty. Had we drawn him as we had first conceived him, Chester’s suspicions would have been entirely justified! But the idea of a little bunny rabbit leaping great heights to sink his fangs into his human victims’ necks seemed just a little too far-fetched, even for us. Besides, logic told us that if there were such a thing as a vampire rabbit, he would most likely be a vegetarian. And so Bunnicula’s victims became carrots and tomatoes and, in one of my favorite scenes in the book, a poor, unsuspecting zucchini! The reason for making Bunnicula mute was simple: It allowed him to remain much more of a mystery.

Writing the book became part of the fabric of our lives, but only one thread among many, and not a major thread at that. Some days we wrote for an hour, some for fifteen minutes. Many days we didn’t write at all. I was occupied with the demands of my work and studies and trying to run a theater and direct plays on the side.

If not exactly occupied, Debbie found herself more and more distracted by the pain she was experiencing in her lower back. The pain grew worse over a period of months, and by the late spring of 1977, it was beginning to make it hard for her to get around. Then, on the twenty-seventh of July, in the middle of the night, Debbie was rushed by ambulance from our apartment in Brooklyn to St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan, her back pain so severe she couldn’t stand or walk. On August eleventh, one day before her thirty-first birthday, we learned that she had a rare form of cancer and that she would not recover.

Debbie remained in the hospital for about two months. In late September, she moved into her parents’ apartment in the Riverdale section of the Bronx, the apartment where she had lived from the age of twelve until she had gone off to college. After a time of shuttling back and forth between Brooklyn where I lived and Manhattan where I worked and the Bronx where my heart was, I found someone to live in our apartment and take care of Gudrun and Moose, and I, too, moved into my in-laws’ home.

For ten months, I spoke to doctors and nurses every day on the phone or in person. Every day, I filled pieces of paper with lists of questions and hastily scribbled notations about symptoms and treatments and pain medications. Debbie would return to the hospital four more times, spending nearly as much time there as she did in her parents’ apartment.

At some point that fall, I typed up the six chapters we had written and, when Debbie was feeling up to it, we returned to telling each other the story of Bunnicula, the vampire rabbit. I can’t place the moment, where it happened or when; in truth, I have no memory at all of writing the book from that time on. I trust that some of it was written in the hospital, some in the apartment in Riverdale. But I can’t see us in my mind’s eye, can’t connect the words on the page to the hands that wrote them. The only connection I can make is to the sound of the two of us laughing as we continued to tell the story aloud to each other.

Typed manuscript page of Bunnicula, with handwritten edits.

There is one other moment I recall. It has more to do with a teddy bear, though, than the writing of Bunnicula. The bear had been mine when I was a child, handed down from my older brothers, so he probably dates from the 1930s. He had button eyes and slots behind his head and arms for fingers to slip into and animate his worn, nubby body. Shortly after Debbie and I had married, I had rescued Teddy from the attic of my parents’ home; during Debbie’s first hospital stay, I gave him to her to be her mascot. She kept him next to her on her bed, where he became a familiar sight to visitors and a constant and comforting friend to Debbie and me.

Teddy, in my arms as a child in Webster.

Many years later, Teddy is still with me. Here he is on a bookshelf in my office, where I see him every day.

Using my fingers and the slots in Teddy’s arms, I brought him to life many times, to cajole Debbie out of her sadness and make me laugh, to turn bad moments on their heads. It wasn’t long before Teddy demanded to know when we were going to write his story. “I’ve had a fascinating life, you know,” he told us. “Your readers would be far more interested in my adventures than those of a silly old vampire rabbit!”

The only way to quiet him down was to promise to write his story. Which we did, of course, not wanting to put up with the nattering of a cranky, egotistical teddy bear any more than we had to. But then, how smart he was to know that we needed something to look forward to as we approached the end of writing Bunnicula.

By the time Debbie died on June 3, 1978, she was the coauthor of two children’s books: Bunnicula, a Rabbit-Tale of Mystery and Teddy Bear’s Scrapbook.

The original covers of Bunnicula and Teddy Bear's Scrapbook.

It was important to her to leave something of herself behind, something to let the world know she had been here.

To those who knew her, she left warmth and light to help us move on without her. To those who would never know her, she left Harold and Chester, a piece of Romanian sheet music, laughter, and words—words, with their power to create characters and worlds, to light up the darkness, and, in the face of impossibility, to make anything seem possible.

A version of this essay, "Writing Bunnicula: The Story Behind the Story", was originally published in 1999 as part of the 20th Anniversary special edition of Bunnicula.